Hops provide two main components to beer, of course: the bitterness and the hoppy aroma. Sierra Nevada beer is well-known (and respected) for using great amounts of whole hop cones, even though only about 25% of the potential bitterness available from them ends up in the beer. This is known as hop utilization, and it is considered a loss worth tolerating in order that a material as close to nature as possible is employed. Other forms of hops give higher rates of utilization, including hop pellets and hop extracts, though brewers have differing opinions about what forms produce the best beers.

Hope It’s Hoppy

Hops are sensitive and quickly deteriorate. Hence those very cold storage rooms in Chico and Mills River where the hops are packed tightly into sacks and bales to exclude air. In England they call these big sacks hop pockets.

When leaf hops are used, there is a need for an extra vessel in the brewhouse, with the liquid wort flowing through a bed of residual hops on its way to the next stage. This vessel is called a hop back.

The bitter substances derived from the hop don’t only have a role in flavor. They help support foam — and they are antimicrobial. Perhaps the first person to report this was a saint, Hildegard von Bingen.

Hops Aren’t for Everyone

Not all beers are particularly hoppy. For example, helles, one of the main types of lager beer in Germany, is very much “malt forward.” The word hell in German means pale. Another lightly hopped beer is hefeweizen, the wheat-based brew which employs an ale yeast that produces substantial aromas of banana and clove. Think Kellerweis.

Hold the Hydrogen Sulfide

Whilst on the subject of flavor, let us dwell upon higher alcohols, which give wine-like (“vinous”) notes to beer. And hydrogen sulfide, with its aroma of eggs that is undesirable in most beers but much prized in the ales from Burton-on-Trent England.

Both the alcohols and the hydrogen sulfide are produced by yeast in fermentation. In order to control this process, the brewer relies on keeping certain things constant. One control parameter is the amount of yeast that is added to the fermenter. Traditionally this is measured using a hemocytometer, a microscope slide that is marked off into grids. A dilution of the yeast slurry is popped onto the slide and, by peering through the microscope, the cells that are present within a certain part of the grid can be counted. This device got the name it did because it was originally used to count red blood cells.

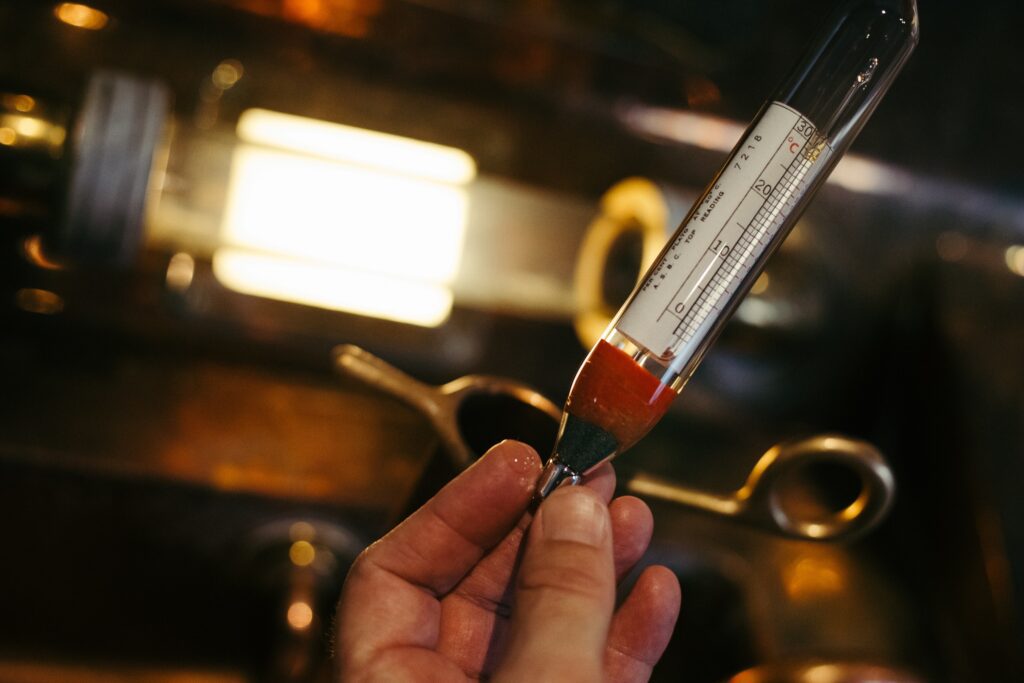

Hydrometers

The time-course of fermentation is traditionally monitored using a hydrometer, a graduated and weighted tube that floats in the fermenting wort. The more sugar in the liquid, the higher the hydrometer floats. As the fermentation progresses, the hydrometer sinks.

Thank goodness for yeast, then. And thank heavens for Hansen (Emil Christian), who was the first person to develop pure yeast cultures when he was with Carlsberg in Copenhagen.

Hazy Beers

So, we talked about hops and yeast. Let us turn to malt. Most of the malts in the world are made by sprouting barley, Latin name Hordeum. One of the main reasons that barley is preferred is that each grain is surrounded by a husk (or hull), which forms a convenient filter bed in the brewhouse.

The name for the main storage proteins in this type of grain is hordein (as in Hordeum). These are the proteins whose digestion products in beer are the entities that folks with gluten-intolerance react to. They are also the proteins that tend to cause haze in beer.

The hordeins are substantially solubilized and digested during the malting process, in which the barley grains grow to a necessary but limited extent as I have pointed out previously. We do not want the shoot (acrospire) to grow so much that it pokes out of the end of the grain. Such grains are called huzzars.

How Does Beer Gush?

Another essential property of the barley is that it should not be contaminated with the mold Fusarium, which produces a small protein called hydrophobin that causes beer to gush (which we talked about last time).

In Japan there are products that contain much less malt than most beers worldwide. These are called happoshu. They were developed because less malt over there means less taxation.

Tax has always been a driving force in the beer world. Back in the 18th century in England, coarse malt, dried over burning wood, attracted less taxation than did malt kilned over cleaner fuel sources. These cheaper malts could be used in less expensive beers purchased by folks with less income, such as the porters in the markets of London. Hence the name porter. One brewer whose name is always linked to porter is Ralph Harwood. When it comes to IPA, the name invoked over there is George Hodgson. For both gentlemen, the reality is probably that we can take some of the claims for their roles in developing these beers with a pinch of salt.

– Charlie Bamforth