Perhaps you started as a casual fan of craft beer, but at some point it fully captured your imagination. The pros make great stuff, you think, but maybe I can homebrew something stellar.

You absolutely can, and if you need a place to start, try our Sierra Nevada Pale Ale homebrew recipe. And while that beer put Cascade hops on the map, the secret hero behind Pale Ale is the yeast. There’s the obvious reason: through fermentation, yeast creates alcohol. (Otherwise you’re stuck with sugary wort.) But Pale Ale’s yeast influences the aroma and flavor, with its hallmark bottle conditioning also creating the final carbonation and protecting against off-flavors.

Considering those impacts, choosing the right yeast takes some thought as you plan your homebrew. Are you making an ale or lager? Going for clarity or hazy? Soft or dry finish? Asking the right questions will help narrow down the hundreds of options, and we’ll highlight several key factors to help guide your search.

Beer Yeast

Brewing yeast is a unicellular fungus that takes the sugars you’ve coaxed from barley and enjoys a feeding frenzy, converting them into ethyl alcohol (ethanol) and carbon dioxide. Specific types of yeast are responsible for beer’s two main fermentation groups, ales and lagers.

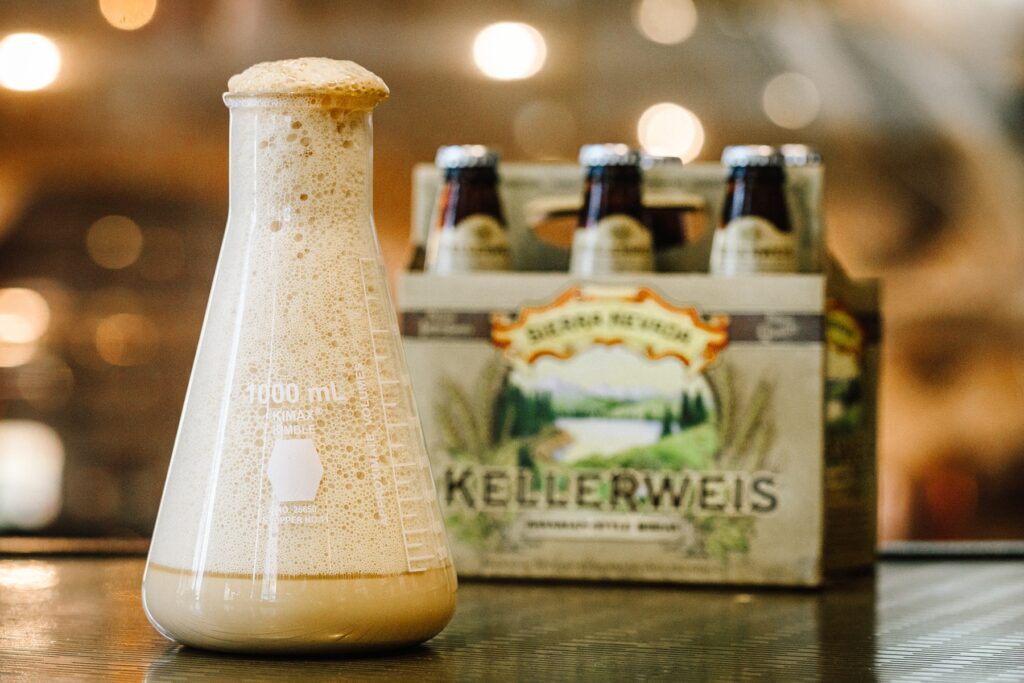

Saccharomyces cerevisiae is the species for ales, called “top fermenting” because the yeast action collects in a foamy layer at the top of the vessel. Lager uses a “bottom fermenting” yeast called Saccharomyces pastorianus — calmer, slower, and settling at the bottom of the vessel. And while ale yeast generally likes warmer temperatures and lager prefers the cold, you’ll see below that each strain has its preferences.

Factors to Consider in Choosing Yeast for Brewing

Flavor and Aroma, of course!

“Brewing strains have to have a wide range of traits,” says our founder Ken Grossman in his book Beyond the Pale, “first and foremost the ability to produce good flavor and aroma compounds…”

The end game is a tasty beverage, so flavor is the foundation when selecting yeast. Certain styles have well-defined parameters, like the wheat-based hefeweizen whose yeast of German origin is responsible for hallmark aromas of banana and clove. Or when you get spicy notes of black pepper from a Belgian saison, that’s often the yeast. But it’s up to your creativity and palate with many other styles.

For Sierra Nevada Pale Ale, after much trial and error, Ken went with Chico ale yeast in part because of pleasant floral aromatics created during bottle conditioning. “I even get a little bit of fresh apple,” says Terence Sullivan, our Product Manager who’s been with Sierra Nevada since 1994. Those nuances blend with hop-driven notes of pine and grapefruit for an all-together dynamic brew that, decades later, is still the one you’re proud to share.

Fermentation Temperature

Beer yeast strains have ideal temperature ranges that deliver the best results. Too warm and you risk off-flavors or dominant traits that overshadow the whole; too cold and yeast only hobbles along or outright quits fermenting. Ale yeast is generally optimal between 60–75 ºF, while lager yeast favors a chilly 42–55 ºF. Homebrew yeast suppliers will often get even more specific, like this California ale strain (read: Chico yeast) suggesting 64–73 ºF.

So be mindful of your local climate and storage conditions for fermentation. Corner of a dark basement or closet? Solid choice. Sun-drenched apartment with no air conditioning? Consider cooling jackets or other gear to keep your temps steady — and sunlight out!

Alcohol Tolerance

Yeast creates the alcohol, sure, but how much alcohol ultimately affects the performance of yeast strains. If your recipe aims for a soaring ABV, like Hoptimum Triple IPA (11% ABV) or our other High Altitude beers, choose a yeast that’s suited for those burly environments. If you brew high-gravity wort, but choose a yeast strain with a lower alcohol tolerance, the yeast can’t effectively finish its fermentation job. You’re left with an uber sweet beer destined for the drain.

Attenuation

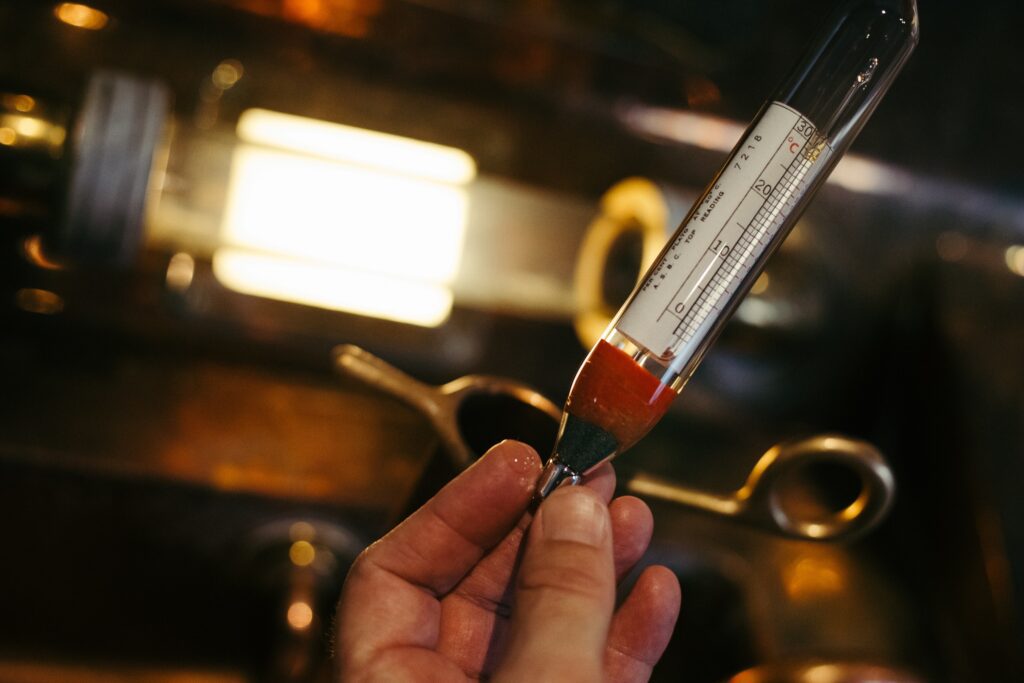

Before adding yeast to your homebrew, you’ll likely measure the “original gravity” with a hydrometer. This tells you how much fermentable sugar is in the wort, and attenuation is what percentage of that sugar a yeast strain converts into alcohol and CO2. If yeast achieves 75% attenuation, for example, only a quarter of the sugars remain in the liquid.

Depending on the style you’re brewing, or the drinking experience you’re after, attenuation will impact key attributes like body, sweetness, and finish. With a beer like Crisp Little Thing, as the name implies, high attenuation is critical for that dry and snappy finish. Torpedo IPA, on the other hand, requires less attenuation for its medium body and malt sweetness that balances the bitter hops.

Flocculation

Yeast cells glom together during fermentation, and this flocculation results in the yeast either rising to the top of the vessel or sinking to the bottom. High flocculation — when yeast readily gathers and falls away — is helpful for pilsner styles like Summerfest where the goal is bright and brilliant beer. Conversely, a wheat ale like Sunny Little Thing or a Hazy IPA benefits from low flocculation, where some yeast stays in suspension and contributes to the cloudy look of those styles.

For Sierra Nevada Pale Ale, Ken says flocculation was a main criteria for yeast — especially because he didn’t have a filter in 1980. “We wanted [yeast] that was not fluffy and easily disturbed and floated back up into the beer.”

Selecting Yeast for Beer

Homebrew suppliers take a lot of the guesswork out of choosing a yeast strain. The beer style is often right there in the strain name, and you’ll see the hard numbers around fermentation temperature, alcohol tolerance, attenuation, and flocculation. And while nailing a true-to-style brew is a worthy pursuit, embrace your own sensibilities around aroma and flavor. Try the same recipe with slightly different yeast strains. Or doctor up some total hybrids: this style with that surprising yeast. May your discoveries be delicious.